Measles: The Disease, The Vaccine and The Global Impact

Explore our comprehensive guide on Measles, a highly contagious disease that can lead to severe complications. Learn about its symptoms, transmission, and the importance of vaccination in preventing its spread. Understand the risks, especially for children and adults with compromised immune systems, and the global efforts to eliminate this disease. Stay informed and protect your health.

1) Introduction

Hello there, dear readers! Welcome to our blog,

where we delve into the intriguing, and at times befuddling, world of health

and wellbeing. Today, we're going to look at an issue that's been making news

all around the world: measles.

The measles virus (MV) causes the extremely

infectious condition known as rubeola. With 21 distinct strains known to exist,

this virus is a bit of a shape-shifter. It's a little like a comic book

villain, constantly shifting shape to avoid capture. But don't worry, our

scientists and healthcare specialists are constantly on the case!

This is no easy sickness to deal with. It

appears to begin innocently enough, with symptoms such as a high temperature,

cough, and runny nose. Then it shows its real hues. A rash appears at the

hairline and spreads downhill to cover the majority of the body. Not to mention

the little white dots known as Koplik's spots, which form inside the mouth.

The measles virus is an expert at concealment

and invasion. It infects the host by binding to host-specific receptors via its

H and F proteins. It acts like a miniature Trojan horse, deceiving our cells

into allowing it to enter. Once inside, it multiplies rapidly, wreaking damage

on our bodies.

But here's the catch: Measles can be avoided.

Yes, you read that correctly. We have the ability to halt the spread of this

illness. Our defense against this invader is the measles, mumps, and rubella

(MMR) vaccination, which is around 97 percent effective at preventing measles

after two doses.

Despite this, measles remains a global issue,

killing over 100,000 people each year. What's the reason? Lower vaccination

rates in some communities, making more individuals susceptible to the disease

and diminishing herd immunity.

So, dear readers, let us arm ourselves with

information and act. Let us guarantee that we and our loved ones are immunized.

Let us spread the word about the need of vaccination not only for our own

health, but also for the health of our communities. Stay tuned for future pieces

that will go deeper into the realm of measles. We'll look at the disease's

science, the need of immunization, and much more. We can make a difference if

we work together. Welcome to our exploration of the world of measles!

The earliest recorded record of measles in the

United States was made in 1657 by a Boston, Massachusetts resident. By the

early twentieth century, measles was responsible for around 6,000 fatalities

each year in the United States. Prior to the introduction of a vaccine,

virtually all children had measles by the age of 15, resulting in an estimated

3 to 4 million cases in the United States alone per year.

The discovery of a vaccine in the mid-twentieth

century was a watershed moment in the history of measles. During a measles

outbreak in Boston, Massachusetts in 1954, John F. Enders and Dr. Thomas C.

Peebles identified the virus. They developed a vaccine using this strain,

called as the Edmonston-B strain. The first measles vaccine was licensed for

general use in 1963 after successful testing. In 1968, an enhanced version of

the vaccine was introduced.

The advent of the measles vaccination resulted

in a considerable decrease in the disease's incidence. The Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention (CDC) established the aim of eradicating measles in the

United States in 1978. Although the target date was not realized, widespread

use of the measles vaccination significantly decreased illness rates. By 1981,

the number of reported measles cases had dropped by 80% from the previous year.

Measles was declared eradicated in the United States in 2000, indicating that

there had been no continuous disease transmission for more than 12 months. This

was a remarkable accomplishment made possible by the United States' extremely

effective immunization program and enhanced measles control in the Americas

area.

However, the battle against measles is far from

done. Despite the availability of a highly effective vaccine, measles outbreaks

continue to occur, particularly in low-vaccination-rate regions. These

outbreaks highlight the critical significance of maintaining high vaccination

coverage in order to prevent the recurrence of this potentially lethal illness.

Finally, the history of measles demonstrates

the power of scientific discovery and public health action. Measles, which was

formerly a prevalent and frequently fatal illness, has been almost eradicated

because to the invention and widespread use of a vaccination. The ongoing

occurrence of outbreaks, on the other hand, serves as a reminder of the need of

vaccination in limiting the spread of this extremely dangerous illness.

Prior to the 1963 release of the measles

vaccine, significant outbreaks occurred every two to three years, resulting in

an estimated 2.6 million fatalities per year. Despite the availability of a

safe and cost-effective vaccine, a projected 128,000 individuals died from

measles in 2021, the majority of whom were children under the age of five.

Accelerated vaccination efforts by governments,

WHO, and other international partners averted 56 million deaths between 2000

and 2021. Measles mortality reduced from 761,000 in 2000 to 128,000 in 2021 as

a result of vaccination.

More than 140,000 people died from measles in

2018. The vast majority of measles deaths (more than 95%) occur in nations with

poor per capita incomes and inadequate health-care facilities.

Measles immunization avoided 17.1 million

deaths globally between 2000 and 2014, a 79% reduction. Measles is expected to

infect 9 million individuals worldwide by 2021. For more than 50 years, safe

and effective vaccinations against measles and rubella have been available.

Between 2000 and 2021, measles immunizations saved more than 56 million lives

globally.

The average number of measles cases recorded in

the United States every year was 130. The vast majority of case-patients from

the United States were unvaccinated (74%). In the United States, it is

predicted that 9,145,026 children (13.1%) are vulnerable to measles. If no

attempt is made to catch-up with pandemic vaccination rates, 15,165,221

youngsters (21.7%) will be vulnerable to measles.

Global coverage with regular first-dose MCV

(MCV1) grew from 72% to 85% between 2000 and 2019.

These figures emphasize the need of maintaining

and boosting vaccination rates in order to prevent the spread of measles and

minimize the number of fatalities caused by the illness.

2) Measles

Virus

a) Classification and Structure of Measles

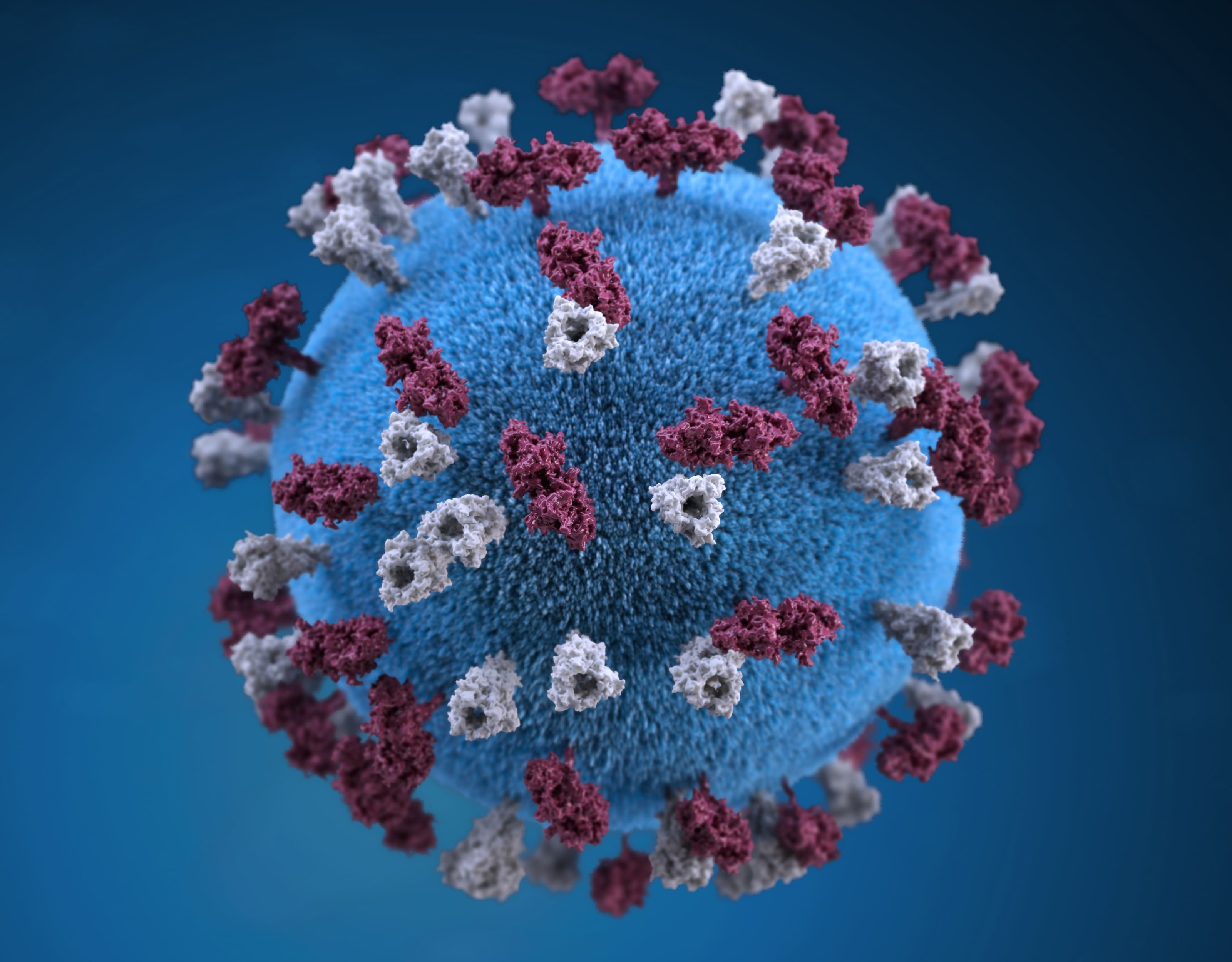

MeV is a member of the Morbillivirus genus,

which is part of the Paramyxoviridae family. The Paramyxoviridae family has two

subfamilies: Paramyxovirinae and Pneumovirinae. The subfamily Paramyxovirinae

is further subdivided into seven genera. The genome of the measles virus is

generally 15,894 nucleotides long and encodes eight proteins. The World Health

Organization (WHO) presently recognizes eight measles clades (A-H), with 23

subtypes.

On the viral surface, there are two envelope

glycoproteins: hemagglutinin (H) and membrane fusion protein (F). These

proteins are in charge of binding to host cells and invading them. The H

protein is responsible for receptor attachment, while the F protein is

responsible for viral envelope and cellular membrane fusion. Furthermore, the F

protein can induce infected cells to directly merge with nearby uninfected

cells, resulting in the formation of syncytia.

b) Genome and Proteins of Measles

The genome of the measles virus is generally

15,894 nucleotides long and encodes eight proteins. The WHO presently recognizes

eight measles clades (A-H). Subtypes are denoted by numerals such as A1, D2,

and so on. There are now 23 identified subtypes.

P, an important polymerase cofactor, and V and

C, which have many activities but are not absolutely necessary for viral multiplication

in cultured cells, are encoded by the measles virus (MV) P gene. The V protein

is not connected with intracellular or released viral particles and is

translated from an altered P mRNA.

c) Pathogenesis and Transmission of Measles

Measles is a very infectious illness spread by

respiratory aerosols. The virus first infects CD150+ lymphocytes and dendritic

cells in circulation and lymphoid organs, then spreads to nectin-4 expressing

epithelial cells.

In previously uninfected humans and nonhuman

primates, the virus produces systemic illness. Measles is marked by fever and a

skin rash, as well as cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis. The transitory immune reduction

caused by measles makes people more susceptible to opportunistic infections.

Measles is so contagious that if one person

gets it, up to 90% of those in close proximity who are not immune will also get

it. Infected persons can infect others four days before and four days after the

rash emerges. After an infected individual leaves a location, the measles virus

can survive in the air for up to two hours.

3) Clinical

Features of Measles

Rubeola, or measles, is a highly infectious

viral virus that predominantly affects youngsters. It is distinguished by a

widespread skin rash and flu-like symptoms. The major location of infection in

the lungs is alveolar macrophages or dendritic cells. The measles virus travels

to regional lymphoid organs after initial replication in the lung, resulting in

systemic infection.

a) Symptoms and Signs of Measles

Measles symptoms usually occur 10 to 14 days

after being exposed to the virus. A high fever, cough, runny nose, and red,

watery eyes (conjunctivitis) are the first signs. Koplik's spots, which are

small white spots that may form within the mouth two to three days after the beginning

of symptoms, are frequently associated with these symptoms.

A rash generally appears three to five days

after the initial symptoms, appearing as flat red patches on the face at the

hairline and extending downhill to the neck, torso, arms, legs, and feet. On

top of the flat red dots, little raised bumps may form. As the spots travel

from the head to the rest of the body, they may become connected. When the rash

occurs, a person's temperature may reach 104° Fahrenheit.

b) Incubation Period for Measles

The incubation period for measles, which is the

time between exposure and the development of symptoms, is 11 to 12 days on

average. The average duration between exposure and rash start is 14 days, with

a range of 7 to 21 days. The measles virus spreads in the body throughout the

incubation period, although there are no signs or symptoms of measles.

Measles complications can be severe, especially

in children under the age of five, individuals over the age of twenty, pregnant

women, and those with impaired immune systems. Ear infections and diarrhea are

common problems. Severe problems include pneumonia (lung infection) and

encephalitis (brain swelling), which can result in hospitalization and even

death.

One in every five unvaccinated persons in the

United States who contract measles is hospitalized. Pneumonia, the most

prevalent cause of mortality from measles in young children, affects as many as

one out of every twenty children infected. One in every 1,000 children who have

measles will develop encephalitis, which can cause convulsions and leave the

kid deaf or intellectually disabled.

Long-term effects of measles include subacute

sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), an extremely rare but devastating central

nervous system condition caused by an earlier measles virus infection. SSPE

often occurs 7 to 10 years after a person has measles, even if the person

appears to have recovered completely from the infection.

4) Clinical

Diagnosis of Measles

Measles is an acute viral respiratory infection

marked by a fever and malaise prodrome, cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis,

generally known as the three "C"s. A maculopapular rash follows a

pathognomonic enanthema, Koplik dots. The rash typically starts 14 days after

exposure and progresses from the head to the trunk to the lower limbs. Patients

are infectious from four days before to four days after the rash emerges.

Immunocompromised people may not get the rash at all.

The disease's distinctive rash, as well as a

tiny, bluish-white patch on a bright red backdrop — Koplik's spot — on the

inside lining of the cheek, may typically be used to identify measles. The

provider may inquire if you or your kid has had measles immunizations, whether

you have recently gone abroad outside of the United States, and if you have had

contact with somebody who has a rash or fever.

a) Laboratory

Confirmation of Measles

All sporadic measles cases and outbreaks

require laboratory confirmation. The most popular procedures for confirming

measles infection are the detection of measles-specific IgM antibody in serum

and measles RNA by real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in a

respiratory samples. At the time of first contact, healthcare practitioners

should collect a blood sample as well as a throat swab (or nasopharyngeal swab)

from individuals suspected of having measles. Urine samples may also contain

the virus, and collecting both respiratory and urine samples, when possible,

might improve the probability of identifying the measles virus.

b) Serologic Testing for Measles

The presence of particular IgM antibodies in a

serum samples taken during the first few days of rash development can give

presumptive proof of a current or recent measles virus infection. However,

because no assay is 100% specific, serologic testing of non-measles patients

using any assay may provide false positive IgM findings on occasion. Serologic

tests can potentially provide false-negative results if serum specimens are

taken too soon after the commencement of the rash.

Both IgG and IgM antibodies develop within 3-7

days of the commencement of a primary infection. Both antibodies then rise

until they reach a plateau 2-3 weeks later. Antibody levels can be reported as

Non-Reactive (no detectable antibody), Indeterminate (the degree of antibody

observed is borderline reactive or equivocal), or Reactive (the antibody is

detectable within the assay's positive range).

c) Genotyping of Measles Virus

During epidemic investigations, measles viral

genotyping can be useful in tracking transmission paths. The findings of

genotyping can assist confirm, deny, or uncover links between instances. If two

instances contain identical N-450 sequences, they may be linked even if the

link is not clear. Measles virus genotyping can also assist determine which

foreign country is responsible for an imported case in the United States.

However, genotyping alone is insufficient since one genotype might exist in

several nations and even parts of the world. To establish whether nation may be

the source of an imported US case, genotype data should be analyzed in

conjunction with epidemiological information such as travel and exposure histories.

5) Epidemiology

of Measles

Measles is a contagious viral illness that was

originally reported in the seventh century. Prior to the availability of a

vaccine, measles virus infection was practically ubiquitous during infancy, and

more than 90% of people were immune due to previous infection by the age of 15

years. In underdeveloped nations, measles is still a frequent and often fatal

disease. According to the World Health Organization, there were 142,300 measles

fatalities worldwide in 2018.

Measles is a highly infectious virus that

dwells in the mucus of an infected person's nose and throat. Coughing and

sneezing might transmit it to others. Other individuals can become sick if they

breathe contaminated air or contact an infected surface and then touch their

eyes, noses, or mouths. Infected persons can infect others four days before and

four days after the rash emerges. After an infected individual leaves a

location, the measles virus can survive in the air for up to two hours.

b) Temporal Pattern of Measles

The seasonality of measles varies by area. In

Guangxi, China, for example, seasonal maxima occurred between April and June,

and a temporal measles cluster was found in 2014. Overall, a two-piecewise

temporal pattern of measles incidence was detected during the whole 11-year

period, with a decrease from 2004 to 2009 and an upswing from 2010 to 2014.

c) Secular Trends in the United States for Measles

Prior to 1963, the United States recorded

roughly 500,000 cases and 500 measles fatalities each year, with epidemic

cycles occurring every 2 to 3 years. However, the true number of cases is

believed to be between 3 and 4 million every year. More than half of people had

measles by the age of six, and more than 90% had it by the age of fifteen.

Measles incidence plummeted by more than 95% in the years after the vaccine's

approval in 1963, and 2- to 3-year epidemic cycles were no longer common. In

2019, 13 measles outbreaks were recorded, accounting for 663 cases; six of

these outbreaks were connected with underimmunized close-knit groups,

accounting for 88% of all cases.

Measles outbreaks continue to occur as a result

of the disease's high contagiousness and the existence of unvaccinated

populations. The most recent epidemic in the United States occurred in 2019,

largely among unvaccinated persons. Outbreaks can also develop in areas with

unvaccinated populations. For example, in 2015, a measles epidemic occurred at

a child care center in Illinois, when virtually all of the unimmunized infants

under the age of one year caught the disease. Globally, measles epidemics can

cause serious complications and fatalities, particularly in young, malnourished

children. Cases imported from other countries continue to be a major source of

infection in nations nearing measles eradication.

6) Surveillance

and Reporting for Measles

Surveillance and reporting are critical

components of public health, especially when it comes to infectious illnesses

like measles. Surveillance is the continuous collecting, analysis, and

interpretation of health data, which is required for planning, executing, and

evaluating public health initiatives. Measles cases in the United States are

reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) via the

National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) by states. Every

confirmed measles case should be subjected to active monitoring to ensure

prompt reporting of suspected cases in the population.

As the number of measles cases declines, so

does the need of monitoring. As a result, a thorough laboratory analysis of

probable measles cases is a critical component of measles eradication

initiatives.

a) Case Identification for Measles

Case detection is an important stage in disease

surveillance. It entails identifying and documenting probable cases of a

disease. A clinical case definition has been devised in the context of measles

to help in identification. Anyone with a fever, widespread maculopapular

(non-vesicular) rash, cough, coryza (runny nose), or conjunctivitis (red eyes)

is suspected of having measles. The distinction between imported and indigenous

cases becomes increasingly significant when the success of stopping indigenous

measles transmission is measured. Identifying suspected measles patients is

critical during a measles eradication campaign, especially given the low

clinical suspicion of measles.

b) Data Collection for Measles

Data gathering is an essential component of

monitoring and reporting. It entails obtaining extensive information about each

patient, such as demographics, clinical symptoms, immunization history, and so

on. The information gathered is utilized to confirm measles cases, including

critical clinical information such as the date of beginning of symptoms, date

of sample collection, and measles vaccination history necessary. During case

investigation, the measles surveillance worksheet should be used as a guideline

for gathering demographic and epidemiologic data. Surveillance data is also

used to summarize current measles epidemiology and to evaluate preventative

programs and attainment of goals such as disease eradication.

c) Reporting Procedures for Measles

When a case is discovered and data is gathered,

it must be reported to the proper health authorities. In the United States,

measles cases should be reported to the CDC as soon as possible (within 24

hours) by the state health department. Measles, for example, must be reported

to the Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

State legislation requires health care practitioners, health care institutions,

medical labs, and, in some cases, veterinarians and veterinary medical

laboratories to report disease to the health department. The reporting of measles

cases is critical for tracking the disease's transmission, adopting control

measures, and assessing the efficacy of preventative programs. It is also

critical for maintaining public and health-care professional awareness.

7) Prevention and

Control of Measles

The primary means of preventing and controlling

the spread of measles is to ensure community vaccination. The measles

vaccination, which is frequently delivered as part of the MMR vaccine, is the

most effective strategy to prevent the disease. The Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention (CDC) advises that children take two doses of the MMR

vaccination, the first at 12 to 15 months and the second at 4 to 6 years. Teens

and adults should also have their MMR immunizations up to date. Aside from immunization,

timely identification and isolation of individuals with known or suspected

measles is critical in limiting disease transmission. This involves following

conventional precautions including airborne precautions in hospital

environments.

MMR vaccination is extremely safe and

effective. Two doses of the MMR vaccination are around 97% effective in

preventing measles, whereas one dose is approximately 93% effective. The first

dosage is usually given between the ages of 12 and 15 months, and the second

dose between the ages of 4 and 6 years. The second dose, however, can be

administered as soon as 28 days following the first. Adults born before 1957

are almost always immune since they were exposed to measles as children. Those

born in 1957 or after must have received at least one dose of the MMR

vaccination. Certain populations, including college or university students,

overseas tourists, and healthcare workers, are advised to have two doses of the

MMR vaccination.

b) Post-exposure Prophylaxis for Measles

PEP is a preventative medical treatment that

begins promptly after exposure to a pathogen (such as the measles virus) to

avoid infection or sickness. PEP for measles can be administered as the MMR

vaccination within 72 hours of initial exposure, or as immunoglobulin (IG)

within six days. However, the MMR vaccination and IG should not be given at the

same time, as this renders the vaccine ineffective. The type of PEP used and

the requirement for quarantine are determined by the individual's age,

immunological condition, and time after exposure. Non-immune babies under 6

months of age, for example, should be administered intramuscular immunoglobulin

(IMIG) and isolated at home for 28 days following the previous exposure if it

happened within three days. If the exposure happened during the previous 4-6

days, IMIG should still be administered, but the quarantine time is lowered to

21 days.

c) Isolation

and Precautions for Measles

Patients with known or suspected measles should

be admitted to an airborne infection isolation room (AIIR) right away. If an

AIIR is not available, the patient should be relocated to an institution that

does. In the meanwhile, the patient should be placed in a private room with the

door shut. Patients with measles should use airborne precautions for four days

after the rash appears. Immunocompromised patients with measles should continue

to use airborne precautions for the length of their illness due to extended

viral shedding. In healthcare settings, regardless of presumptive immunity

status, all workers entering the room of a measles patient should employ

respiratory protection consistent with airborne infection control protocols.

8) Measles in

Specific Populations

a) Infants,

Children, and Adolescents

Rubeola, or measles, is a highly infectious

sickness that predominantly affects youngsters. It is caused by a virus and is

distinguished by a widespread skin rash and flu-like symptoms. A hacking cough,

runny nose, high fever, and red eyes are typical of a measles illness. Before

the rash appears, children may have Koplik's spots (little red patches with

blue-white centers) within their mouth. The rash appears 3-5 days after the

symptoms begin, frequently in conjunction with a high temperature of up to

104°F (40°C). Measles is highly contagious, with 9 out of 10 unvaccinated

persons at risk of contracting it if they come into contact with an infected

person. When others breathe in or come into direct touch with virus-infected

fluid, such as droplets blasted into the air when someone with measles sneezes

or coughs, the virus spreads.

The greatest approach to prevent children

against measles is to get them inoculated. Measles protection is included in

the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) or measles-mumps-rubella-varicella (MMRV)

vaccines given to most children when they are 12 to 15 months old and again

when they are 4 to 6 years old. Approximately 95% of patients gain immunity

after their first immunization, with the remainder developing immunity during

their second vaccination. Immunity is permanent.

Adults over the age of 20 are more prone to get

measles complications. Ear infections and diarrhea are common problems, but

pneumonia and encephalitis are dangerous. One in every five unvaccinated

persons in the United States who contract measles is hospitalized. Pneumonia,

the most prevalent cause of mortality from measles in young children, affects

as many as one out of every twenty children infected. One in every 1,000

children who have measles will develop encephalitis (brain swelling), which can

cause convulsions and leave the kid deaf or intellectually disabled.

Travelers who have not been completely

vaccinated or who have never had measles are at risk of infection if they

travel overseas to regions where measles is circulating. Getting vaccinated is

the greatest method to protect yourself and your loved ones against measles.

You should plan on being completely immunized at least two weeks before your

trip. If your vacation is less than two weeks away and you are not immune to

measles, you should still obtain the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccination.

Cases of measles in the United States are

caused by unvaccinated overseas tourists. Unvaccinated persons who become ill

in other nations bring the disease into the United States. They can transfer

measles to those who are not immune, which can lead to outbreaks.

To summarize, measles is a highly contagious

illness that can affect people of all ages, but it is most harmful for

newborns, children, adolescents, adults over the age of 20, and unvaccinated

travelers. The most effective strategy to avoid measles and its effects is

vaccination.

9) Real Life

Testimonials and Stories of People who have suffered from Measles

Brenda Shaw had measles as a

four-year-old in 1950, an incident that changed her life forever. The illness

caused her eardrum to break, rendering her deaf in her right ear. This issue

has generated problems that she is still dealing with. Brenda spent a month in

the hospital due to a burst eardrum caused by the measles illness. Despite

having two eardrum transplants, she is still deaf in her right ear. The

infection's consequences frequently lead her to experience dizziness and nausea.

Vertigo, a disorder that creates a spinning sensation or loss of balance, can

be caused by problems in the inner ear or brain. Nausea is a typical side

effect of vertigo.

Brenda's episode of measles was

not a unique one. During the outbreak in 1950, her best friend became sick and

suffered lifelong eye impairment. Another student experienced hearing loss in

both ears. There was no measles vaccination available at the time.

Brenda's personal experience with

the serious consequences of measles has made her a staunch supporter of

immunization. "For God's sake, vaccinate your children," she says,

urging parents to vaccinate their children against measles. It is not the cause

of autism." This comment is in reaction to the widely debunked 1998 study

by Dr. Andrew Wakefield that linked immunizations to autism. In 2010, the

medical publication The Lancet withdrew the report, which was regarded as a

"elaborate fraud" by other researchers.

Measles is one of the most

infectious illnesses on the planet, and it may live in the air or on surfaces

for hours. Even before the rash forms, it can be spread by coughing or

sneezing. Blindness, encephalitis, and severe diarrhea are all serious symptoms

of a measles infection. One in every ten persons infected with the illness may

develop ear infections or pneumonia, and one in every 3,000 will die from

respiratory or neurological problems.

Brenda's experience serves as a

harsh reminder of the disease's potential severity and the need of immunization

in preventing it and its repercussions. Her story emphasizes the importance of

ongoing public health initiatives to maintain high vaccination coverage and to

combat vaccine disinformation.

Maggie's story is a strong

witness to the significance of immunization and the hazards that vulnerable

people face when others refuse to vaccinate. Maggie, a young cancer patient,

was exposed to measles, a highly infectious illness that may be especially

harmful for people with weakened immune systems.

Maggie's father, board-certified

pediatrician Dr. Tim Jacks, revealed their experience in 2015. Maggie was

undergoing cancer treatment at the time, which included many rounds of

chemotherapy, lumbar punctures, and surgery to insert a port. Maggie, while

being completely inoculated prior to her cancer diagnosis, was unable to obtain

more vaccines until her treatments were completed.

The measles exposure happened

during a measles epidemic caused by an unprotected Disneyland visitor. Measles

is very infectious and may live airborne in a room for up to two hours,

infecting someone. It is also contagious four days before the rash begins,

making it difficult to diagnose. Measles complications can be deadly, including

ear infections, diarrhea, pneumonia, brain inflammation, and even death.

On January 21, Maggie and her

younger brother Eli, who was too young to get the MMR vaccine, were exposed to

measles. They had to stay in seclusion until February 11 to prevent the

sickness from spreading. The family had to postpone plans and live in terror of

the emergence of measles symptoms as a result of this predicament, which

created tremendous disruption and worry.

Dr. Jacks is frustrated and angry

with parents who refuse to vaccinate their children. He reminded out that their

decisions effect not just their own children, but also vulnerable youngsters

like Maggie. He underlined the importance of "herd immunity," which occurs

when a large percentage of the population is vaccinated, offering some

protection for individuals who cannot receive particular vaccinations, such as

children. Maggie

Maggie's tale emphasizes the

necessity of immunization in reducing the spread of infectious illnesses and

safeguarding vulnerable members of the community. It also emphasizes the

possible repercussions of vaccination apprehension, which may be caused by a

variety of circumstances, including misinformation regarding vaccine safety and

efficacy.

Measles can be especially

concerning for cancer patients due to their decreased immunity as a result of

therapies such as chemotherapy. While effective immunization has reduced

measles incidence, the illness can still represent a major risk to these

people.

Finally, Maggie's tale serves as

a strong reminder of the vital role immunizations play in safeguarding not just

our own health, but also the health of those around us, especially the most

vulnerable people of our community.

Varya, a three-year-old child

from Kazakhstan, had measles when she was three. Alexei and Nastya Naumov, her

adoptive parents, had adopted her from an orphanage despite her severe

sickness, which had rendered her immunocompromised. They had been instructed

mistakenly not to give her several childhood immunizations, including the

measles vaccine, due to her illness.

Varya got red patches on her legs

in February 2019, which were first identified and treated as an allergic response.

When her temperature reached 40 degrees Celsius, an infectious disease

specialist was summoned. She was then diagnosed with hemorrhagic vasculitis,

which was caused by measles.

Varya was sent to an infectious

disease hospital, where she became seriously ill during the following 10 days.

Nastya, Varya's mother, recounts the terrifying time: "Varya was burning

with a fever, crying from pain at night." Varya grew thin and unable to

swallow, weighing barely 17 kg. Her cognitive abilities were damaged by the

extended high-grade fever, which now affects her ability to do her schoolwork.

Varya was in the hospital for six

and a half weeks. The hospital was packed with children and adults suffering

from measles throughout her visit. Nastya still gets upset when she thinks of

Varya's measles struggle, saying, "How would you feel if you saw your

child suffer so much?" "I'm at a loss for words."

In 2019, Kazakhstan had a measles

epidemic with 13,326 cases. Of the 9,409 measles cases reported among children

aged 0 to 14, 7,802 (83%) were unvaccinated. Many were infants who were too

young to receive the measles vaccine. However, vaccination rejection accounted

for 22% of the unvaccinated, while medical contraindications (both genuine and

imagined) accounted for 30%. Unfortunately, the sickness claimed the lives of

nineteen children and two adults.

Varya's trauma occurred about two

years ago, and she is now inoculated and protected against several avoidable

diseases. She has had no bad reactions to any of the immunizations she has been

given.

Varya's tale emphasizes the

significance of immunization, especially in safeguarding vulnerable people like

her. It also emphasizes the possible implications of vaccine misinformation and

the importance of correct vaccination guidance and education.

Cecilia Rodriguez, a Houston

resident, caught German Measles when she was 13 months old, 30 years ago. Her

father, Carlos, first assumed she had a cold because of symptoms such as fever

and a runny nose. Her health immediately deteriorated, and she became unable to

breathe, prompting her parents to hurry her to Texas Children's Hospital.

Cecilia was in a coma for nine

months as a result of the measles virus, during which she underwent many

life-saving but risky procedures. Her speech, hearing, and eyesight were all

affected by the sickness, which had a significant influence on her life. As a

result, she was in special education courses for several years.

Measles is a hazardous disease

that can cause serious consequences such as pneumonia and encephalitis (brain

swelling). These issues might lead to hospitalization and even death in extreme

circumstances. Indeed, roughly one in every three infants infected with measles

will die from respiratory and neurologic problems.

In Cecilia's instance, she was

also advised that the condition would most likely prevent her from having

children. She bucked these expectations, however, and is now a mother of three

children. Cecilia did not give up despite the difficulties she experienced. She

completed her education and volunteered extensively.

Cecilia's measles experience

emphasizes the disease's possible long-term consequences. According to

research, measles can induce long-term immune system damage, resulting in a

type of immunological amnesia that can put children at risk of sickness from

other infections for years. This is due to the fact that the measles virus can

cause a considerable loss of antibodies, which are essential for combating

diseases. It might take 2 to 3 years for the immune system to recover after a

measles infection.

Cecilia's tale emphasizes the

significance of immunization in the prevention of measles. The MMR (measles,

mumps, and rubella) vaccine was not administered to Cecilia until she was 15

months old. Following the 1989 outbreak, which infected 3,200 Texans, the

medical community reduced the age to 12 months. Cecilia now guarantees that all

of her children are vaccinated and up to date because she does not want them to

go through what she did.

Muhammad Ghafoor, a Pakistani

worker, was traumatized when his ten-month-old son, Muhammad Rahim, acquired

measles and was taken to the critical care unit at Benazir Bhutto Hospital's

Paediatric Department in Rawalpindi, Pakistan. Rahim's health was grave, and he

had been on the verge of dying for 14 days.

Rahim first had measles, which

lowered his immune system, and then he got pneumonia. Ghafoor and his wife,

Safina Jan, had first taken Rahim to a government hospital for the first few

prescribed vaccines. However, their dedication waned with time, and they

ignored the measles vaccination, which is generally given to kids at the age of

nine months. As a result, when a measles outbreak arose, Rahim was helpless.

Ghafoor confesses that the

underlying reason of his son's life-threatening sickness was his lack of

information about the need of immunization. He had dismissed immunization as a

minor duty. This lack of knowledge and misunderstandings regarding

immunizations is frequent among low-income and educated households in Pakistan.

Despite huge vaccination

campaigns, measles remains a substantial concern for the unprotected in

Pakistan. According to provincial health officials, eleven children died from

measles in the Rawalpindi district of Pakistan's Punjab province between

January and May, while hundreds were confirmed to be afflicted.

Dr. Mukhtar Ahmed Awan, Director

of Punjab's Expanded Immunization Program, stated that measles is skilled at

exploiting even minor immunity deficiencies. Seven of the 11 children who died

of measles in Rawalpindi were completely unimmunized, while the others had only

gotten a single dosage of the two-dose regimen.

Ghafoor's and his family's story

emphasizes the necessity of immunization in preventing potentially fatal

diseases like measles. It also emphasizes the significance of greater

vaccination awareness and education, particularly in low-income and

under-educated groups.

10) Conclusion

As we conclude our discussion on

measles, we'd want to extend our heartfelt appreciation to all of our readers

who have joined us on this trip. Your enthusiasm and participation have made

our investigation of a crucial public health issue both meaningful and

enjoyable.

We've discussed the history of

measles, its symptoms, and the serious problems it may cause. We've also

emphasized the incredible progress achieved in combatting this disease since

the introduction of the measles vaccine in 1963, as well as the dedicated

efforts of health professionals, policymakers, and parents all across the

world.

Our investigation, however, has

highlighted the persisting problems in the fight against measles. Measles

remains a concern, despite the availability of a safe and effective vaccine,

particularly in places with poor vaccination rates. Maintaining high

vaccination coverage is critical since it not only protects individuals but

also contributes to the larger objective of herd immunity.

We hope that this blog series has

given you useful information and increased your awareness of measles and the

necessity of immunization. We feel that knowledgeable readers like you play an

important role in raising awareness and dispelling myths regarding

vaccinations.

Thank you once more for your time

and interest. We hope to continue providing you with interesting and

thought-provoking information in the future. Stay well, stay educated, and keep

in mind that every vaccine helps in the battle against avoidable illnesses such

as measles.

FAQ’s

Measles is a highly contagious

disease caused by a virus. It can lead to serious complications such as

pneumonia, brain damage, blindness, deafness, and even death, especially in

young children and adults

Measles spreads through the air

when an infected person breathes, coughs, or sneezes. The virus can survive in

small droplets in the air for several hours. You can become infected when you

breathe in these droplets or touch objects contaminated with the virus

3) What are the symptoms of measles?

Symptoms of measles include

fever, cough, runny nose, red and inflamed eyes, loss of appetite, and a rash

that usually starts on the face and neck and spreads to the rest of the body

Measles is diagnosed by a

combination of the patient’s symptoms and laboratory tests. Detection of

measles-specific IgM antibody in serum and measles RNA by real-time polymerase

chain reaction (RT-PCR) in a respiratory specimen are the most common methods

for confirming measles infection

5) Is there a treatment for measles?

There is no specific antiviral

treatment for measles. Management of the disease includes hydration, fever

control, and vitamin A supplementation. If you have been exposed to the measles

virus and have not had the disease or received 2 doses of a measles vaccine,

you should get immunized to prevent the illness

6) How can measles be prevented?

The best protection against

measles is vaccination. The measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine is safe

and highly effective

7) Who should get the measles vaccine?

The measles vaccine is

recommended for everyone age 1 year and older. Certain adults are at higher

risk of exposure to measles and may need a second dose of MMR unless they have

other evidence of immunity

8) What if I have been exposed to measles?

If you have been exposed to the

measles virus and have not had the disease or received 2 doses of a measles

vaccine, you should get immunized to prevent the illness. You need to get the

vaccine within 72 hours after exposure in order to be protected against the

measles virus

9) Can someone get measles more than once?

No, once a person has had

measles, they are immune for life

10) What are the complications of measles?

Complications of measles can

include ear infections, diarrhea, pneumonia, and encephalitis (brain

inflammation). Complications and death are most common in infants less than 12

months of age and in adults

11) How common is measles in the United

States?

Before the measles vaccine was

licensed in 1963, there were an estimated 3–4 million cases each year. Since

2000, when measles was declared eliminated from the U.S., the annual number of

cases has ranged from a low of 37 in 2004 to a high of 1,282 in 2019

12) Can measles be eradicated?

Yes, it's possible. The first

step is to eliminate measles from each country. High sustained baseline measles

vaccine coverage and rapid public health response are critical for preventing

and controlling measles cases and outbreaks

13) What should I do if I think I have measles?

If you have fever and a rash and

think you may have measles, especially if you have been in contact with someone

with measles or traveled to an area with a measles outbreak, have yourself

examined by a health care provider. It is best to call ahead so that you can be

seen quickly and without infecting other people

14) How can I prevent spreading measles to

others?

If you have measles, you can help

prevent spreading it to others by staying at home for at least 4 days after the

rash first appeared, washing your hands regularly, coughing or sneezing into a

tissue or sleeve rather than your hands, and not sharing food, drinks, or

cigarettes, or kissing others

15) Is measles more severe in certain

populations?

Yes, measles can be especially

severe in persons with compromised immune systems. Measles is more severe in

malnourished children, particularly those with vitamin A deficiency

16) What is the home treatment for measles?

Home treatment for measles

includes rest, hydration, fever control, and isolation to prevent spread to

others

17) Can measles lead to death?

Yes, death from measles occurs in

2 to 3 per 1,000 reported cases in the United States. In developing countries,

the fatality rate may be as high as 25%

18) Are there any side effects of the

measles vaccine?

Side effects of the measles

vaccine are usually mild and temporary, such as a fever or rash. More severe

reactions, including allergic reactions, are rare

19) Can measles still be a threat in the

United States?

Yes, since measles is still

common in many countries, travelers will continue to bring this disease into

the United States. Measles is highly contagious, so anyone who is not protected

against measles is at risk of getting the disease

20) What is the global impact of measles?

Measles is a leading cause of

death among children worldwide. Outbreaks in countries to which Americans often

travel can directly contribute to an increase in measles cases in the United

States

Comments

Post a Comment